Marysia Lewandowska

Marysia Lewandowska: Histories Without a Voice

2023

Renowned Polish-born and London based artist Marysia Lewandowska has been the inaugural resident of the Jencks Foundation at The Cosmic House. Lewandowska, whose practice over the past 20 years has explored the public functions of archives, museums and exhibitions was invited to review the holdings of the Jencks archive at a crucial formative time for both the archive and the institution. Starting from the notion of the archive as an open-ended construction of contributions and interpretations, Lewandowska’s artistic research during her residency engaged with the legacy of Maggie Keswick Jencks as it is framed by the multiple histories of The Cosmic House: once a family home, a built manifesto of Post-Modernism and a meeting place for the movement’s main protagonists, and now a museum.

‘Marysia Lewandowska: Histories Without a Voice’, is a transcript of an artist talk at The Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 11 May 2023 presenting her research residency at The Cosmic House.

In every new project, the most important part of the engagement with the institution is the process of invitation. It is in that moment when the approach has been made and the invitation issued that a future project begins to acquire its initial shape. In this first slide, a scene is set by three women who were responsible for making this invitation; they are The Cosmic House director Lily Jencks and daughter of Charles Jencks and Maggie Keswick Jencks, its artistic director Eszter Steierhoffer and trustee Catherine Ince. I met them for the first time during a Salon gathering organised by The Cosmic House in June 2021. The idea of inviting me came from Eszter Steierhoffer who has been aware of my practice exploring archives, interrogating public institutions and re-imagining contributions made by women excluded from the historical narratives.

Let me turn to the site of the residency, the house itself – formerly serving as a family home to Charles, Maggie and their two children, John and Lily. Acquired in 1978, for the following five years the building underwent a major transformation with an aspiration of becoming a built manifesto of Post-Modernism, following a detailed programme devised by architectural historian Charles in collaboration with Maggie and many others. A substantial back garden was designed by Maggie, while the central part of the house, the Solar Stair was developed by architect Terry Farrell, who was involved on the engineering side.

At the bottom of the stairwell, embedded in the floor, sits The Black Hole, a round mosaic by the artist Eduardo Paolozzi, a friend of the Keswick family from Scotland.

In the first few weeks of the residency, while getting to know the house and its contents, something caught my attention and provided what I call the first ‘turning point’. Even though I was very aware of the scope of the original invitation to focus on the contribution of Maggie Keswick (who became Maggie Keswick Jencks in 1978) to the design of The Cosmic House, I was looking for signs of her presence in the house and inside the narrative created by the display. I was conscious of exploring the material traces of an institution at the inception of its becoming a museum. Having worked with different public museums for the last thirty years, I'm always interested in how the values they represent are manufactured and perpetuated. On this occasion I noticed a hand-written pencil inscription on Paolozzi’s design for The Black Hole: ‘For Maggie, happy birthday’. I started my residency on 4 October (my mother’s birthday), Maggie’s birthday is on 10 October. I felt that this moment of commemoration and inception provided a clear direction.

I spent two days each week in the house looking through slides, books and magazines, and meeting people. For the rest of the week there was so much to process: reading typed and hand-written documents and letters, listening to tapes, traversing a vast and unfamiliar terrain of other people’s lives. But I also wanted to bring something to my resultant presentation which has nothing to do with The Cosmic House itself, but has a lot to do with my attention to histories and to the voice.

What you see here is an image of a damaged porcelain coffee cup. This cup is the only surviving object from my grandparents’ home in Warsaw, who survived the Second World War. This irregular black shape on the cup is the residue left by a burning flame which engulfed their house during the bombing of Warsaw. Fleeing the fire, they managed to grab one cup each. An individual’s relationship to history is not the same for each of us. In my family, there is no material trace of history pre-1945. But, of course, because my grandparents and my parents survived, I am here. The awareness of my particular history in relation to a generational gesture of handing down of values has played an important role in this project.

Let’s look at another site, where I continued my research. Within the first three weeks of the residency, I felt that Maggie’s presence in The Cosmic House was very insubstantial. So at the end of October 2021, Lily and I travelled to Portrack, formerly Maggie’s parents’ house in Dumfriesshire, Scotland.

Maggie was born there in 1941 to John and Claire Keswick. After Maggie’s death of cancer in 1995, most of her personal belongings, as well as her archive related to school years, sketchbooks, correspondence, garden-design work, Chinese garden research, photographs, slides and Super 8 films, were moved to Portrack and placed in a separate building. In order to set up a private screening of the films I invited artist and filmmaker David Leister, who is probably the only person in London who has all the equipment to screen any format.

Visiting Portrack House provided another turning point. I was struck by the presence of clocks, and the fact that none of them were chiming. All the clocks were silent, in fact they had been stopped when Maggie died at the age of 53. Here occurred another turning point, as around that time I began thinking of sound and voice as a way of articulating the missing narrative. Lily offered to negotiate with her brother John, who lives in the house, to service the clocks. Once they were moving again, she recorded the chimes so I could use those sounds in a site-specific sound installation I was creating for The Cosmic House.

My ongoing exchanges with Lily and other members of the family led to the building of a necessary trust.

During the first trip to Scotland, I looked through Maggie’s archive.

Charles attempted to assemble a range of disparate materials and make them accessible in what feels like a commemoration room, with a focus on Maggie’s work as a designer. But there is also a lot there that is unsorted, uncurated and easily escaped any classification.

Whenever I encountered this kind of material I kept an open mind as to whether I could use it. I spent time on my own looking through Maggie’s notebooks and sketchbooks, private letters and correspondence with publishers. There was a rich mix of personal and professional material, impossible to disentangle just by looking through it.

In this photograph, Maggie is four years old. Her father is teaching her how to plant; this is a very touching foundational image of Maggie’s lifelong interest in plants, in nature, in gardens.

Maggie Keswick Jencks, photo from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

Maggie Keswick Jencks, photo from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

Even the soap she used to buy was called Fleurs des Alpes, by Guerlain, fitting with the rest of her interests. The design on the packaging reminded me of my mother, who used perfume by the same brand in the 1970s.

These unexpected associations, when my own history and memories overlaid with what I was researching, were special moments. I began to notice how Maggie was presenting herself through photographs and collages, one of them captioned, ‘This book belongs to Maggie Keswick’.

Notebook belonging to Maggie Keswick Jencks

In a scrapbook I found a newspaper cutting with Maggie pictured as one of ‘London’s Smart Girls’.

A series of photographs shows Maggie in 1962 launching a ship accompanied by her father, the chairman of Jardine, Matheson & Co., a trading company based in Hong Kong. Maggie's history was inextricably linked to China through her upbringing and her father’s role and service.

Maggie Keswick Jencks with her parents, photo from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

In the late 60s, her social life was thriving. At the time of Swinging London she opened a fashion shop with a friend, called Anacat. Here you see their invitation to what looks like a great dinner party at the London Planetarium. At this point Maggie is becoming an independent and creative woman.

There was also a writer’s side to Maggie: She read English at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. And there was a design side to Maggie: in 1970 she enrolled at the Architectural Association, London, where she met Charles Jencks.

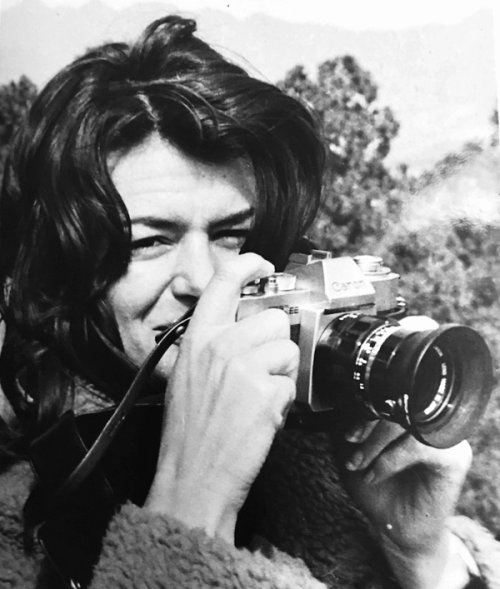

Then came another turning point for me – noticing how much she is present behind the camera.

Alongside writing, designing and drawing, Maggie was an image-maker, constantly taking pictures and documenting, as well as gathering reference material for her book.

Maggie Keswick Jencks, photo from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

In the early 70s she made many trips to China, which led to publishing in 1977 an important book on the Chinese garden, where she explores both its history and philosophy.

In the 1970s it was unheard of for a Westerner and a woman to become an authority on this subject. With the publication of the book, Maggie established herself as a public intellectual: being interviewed by the BBC, giving lectures in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Hong Kong.

In 1987, in Vancouver, she gave a lecture which was audio recorded.

Coming across that recording provided another turning point for me: I heard Maggie’s voice for the first time. It is also when her personality as a passionate public speaker was revealed to me.

Maggie used watercolours during her travels and in her work related to garden design.

In 1988 she was diagnosed with cancer. Maggie’s interest in Chinese cosmology and her referencing of the Dao philosophy, which means ‘the way’, became more frequent and profound then. You can detect that in her multiple drawings of the scholars’ rocks which she was surrounded by both at Portrack, where they were part of her parent’s collection, and later at her and Charles’ home. There's a sense of thinking through very deep time, as in ancient Chinese culture, in which one does not think about the next week, month or year; it's thinking ahead a thousand years.

Chinese scholar's rocks at The Cosmic House

A set of unopened Kodak processing envelopes addressed to Mrs Charles Jencks at 19 Lansdowne Walk provided another moment of troubled reflection for me: Why were these never opened? What did they contain? And, more disturbingly, the envelopes demonstrated how Maggie’s identity disappeared into a ‘wife-shaped void’. The contents were Super 8 films, a typical format for home movies. Lily and I watched the films for two or three hours, and her two young children accompanied us for a while. I was witnessing a generational continuity live as well as recorded. We never see Maggie in the films – she is behind the camera. And she's an excellent filmmaker: patient, attentive, steadily letting the scene unfold.

This early encounter had reaffirmed my desire to both recover Maggie Keswick from Mrs Charles Jencks and to discover how the two were related.

It led me to start looking for signs of Maggie’s role in the 1978 transformation of the house at Lansdowne Walk. This set of staged photographs taken during a shoot for a magazine article shows the couple sitting at the dinner table in what is known as the Summer room. Maggie is pictured with her notebook, which I later discovered contains details of the house’s design, logistics of construction, choice of finishes and furnishings.

Notebook belonging to Maggie Keswick Jencks

View of Time Garden at The Cosmic House designed by Maggie Keswick Jencks

Apart from being involved in the design process and project management, Maggie often participated in Charles’ intellectual journey during numerous trips to East Asia. Europe and the United States, while carrying out her own research. Here is a picture taken during one such occasion in 1981, showing Maggie and Charles after a lecture at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the photograph was taken by a well-known Polish photographer Eustachy Kossakowski.

During my residency I encountered mostly analogue materials, which I very much welcomed.

Despite not being physically stable, they clearly express their own technological past. Seeing these for the first time offered a particular kind of excitement. No one had pre-selected or curated any of it for me, so I could begin from anywhere, introducing and inventing my own methods. You feel an inexplicable pull, a tug or an inner hunch without a promise that it will lead anywhere.

Material from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

After my very first visit to Portrack in October 2021 Lily and I brought all of the audio tapes to London with the intention of having them digitised. Amongst them were ‘Portrack Seminars’, another incredibly rich part of Charles' and Maggie’s life.

The Portrack Seminars in Portrack, Scotland

Maggie Keswick Jencks in Portrack, Scotland

Material belonging to Maggie Keswick Jencks from the Keswick Jencks family house in Portrack, Scotland

Halfway through my research residency, I organised a workshop on the theme of ‘voicing the archive’.

I invited art historian Catherine Grant and curator Jess Fernie – both have done work around women's histories, the public realm and archives – artist Ella Finer, herself working with voice and sound, and artist/curator Karen Di Franco, who presented her research on Carolee Schneemann. This very intimate session helped me to gain confidence through mutual exchange with peers as well by testing early ideas for the possible public outcomes.

Catherine Grant, Karen Di Franco, Lily Jencks, Jess Fernie, Ella Finer, and Eszter Steierhoffer in Time Garden at The Cosmic House

In June 2022, another turning point occurred during a second trip to Portrack. I unexpectedly came across a notebook which Maggie kept between 1982 and 83 – exactly during the transformation of The Cosmic House. If I needed any evidence of Maggie’s actual involvement in the design and realisation process, it was to be found there.

This brings me to the first of the two site-specific audio artworks I made as a result of the research residency at the house. I used the notebook as an invitation to engage with its content, and chose voicing as my method of displaying it. Artist Ella Finer (http://www.ellafiner.com) whose practice has for many years been invested in sound, has lent her voice and read out the content of pre-selected pages. My instruction was that she reads out everything she could see on the page; including the colour of the Biro ink, every punctuation mark, every swish and arrow. So that you could visualise the notebook without seeing it. Her voice guides our imagination through endless lists of taps, lamps, fabrics, carpets, fittings. Listening to her is one way of acknowledging Maggie’s significant contribution to the conceptual as well as actual work carried out during the transformation of the house. This recording is played in Maggie’s former study on the first floor of The Cosmic House.

The second audio work was conceived as an imaginary introduction to the house–museum by Maggie herself. Its source material is an audio recording of a lecture Maggie gave in Vancouver on the history and philosophy of Chinese gardens. The more I listened to that recording, to the passionate and tender delivery, the more I became committed to work with it. This is, ultimately, what an artist has licence to do: provide access to history by way of fiction.

So what I ended up doing was constructing a narrative by editing the existing recording in a new way. This construction had to first work as a written text. I was assisted by Wing Chan, a book editor from Hong Kong, as we experimented with the sequencing in a ‘cut and paste’ analogue way.

Once we finalised the new narrative, the sound edit could begin. Collaborating with Robert Jack, an incredibly skilled and sensitive sound editor, we set out to create a convincing audio introduction to the Cosmic House given by Maggie at an unspecified time. In the final piece, installed in the Spring room, her voice is emitted from the existing concealed loudspeakers. These belong to the architecture of the house, and had never been previously used by the museum. The fifteen-minute recording begins with the sound of a chiming clock and ends with that sound played backwards.

I wanted the project to open on 10th of October – Maggie’s birthday, of which I learnt from Paolozzi’s dedication.

Opening of how to pass through a door at The Cosmic House

My first turning point became the beginning of the public presentation celebrating Maggie’s intellectual and artistic contribution to the house. Visitors receive a free booklet, allowing for a self-guided visit. In collaboration with graphic designer Stefan Andersson (https://www.karlstefanandersson.com/) I have created a companion publication, acting as a souvenir of the visit, highlighting the role Maggie played in the transformation and the subsequent cultural and social life of the House. It contains a transcript of the text spoken by Maggie in one of the audio works, together with an image of the sound wave which discreetly gives away how the original Maggie’s lecture recording from Vancouver was re-imagined.