Charles Jencks

Semiology and Architecture

1969

‘Architecture and Semiology’ featured in the 1969 volume entitled Meaning in Architecture, co-edited by Charles Jencks and George Baird. Essays contained in this book explore the relationship between architecture and its social meaning with recourse to semiology, linguistics, cybernetics, and information theory. In this contribution Jencks put forward his ideas about architecture’s capacity to act as a language, communicating meaning to its users and surroundings. The relationship between architecture and meaning continued to be of central concern in Jencks’ work in the following years.1

Charles Jencks, ‘Semiology and Architecture’, in Meaning in Architecture, ed. George Baird and Charles Jencks (New York: George Braziller, 1969).

Meaning, Inevitable yet defined

Once, when travelling in France, I had a rather unnerving experience which I am unlikely to forget. A French companion turned to me suddenly and pointed toward the spire of a cathedral which had just come into view: ‘Jetez un coup d’oeil sur cette flèche!’ The glance was painfully exquisite; literally, ‘Throw a blow of eye on top of that spire.’ I could suddenly see my eyeball wrenched from its socket and thrown across the field to be impaled on that pin-sharp point. But my companion was completely laconic. He had just meant ‘Look at that spire,’ and no such ludicrous sensations were reverberating through his head, because to him the metaphor was almost dead. The signs that were deeply embedded in the French language were partially asleep and inaccessible to him. Whereas to myself suddenly they were awake in that raw state of freshness, even wetness, of the newly born.

Later it occurred to me, on hearing further metaphors, that every Frenchman was a natural genius; particularly so because his creative talent was conveyed with such complete insouciance and candour. But then on further thought it became clear that the whole environment, including language, is always in this ambiguous state of limbo – somewhere between life and death. Every dead form that one can perceive is a sign waiting to be resuscitated. As Braque said: ‘Reality only reveals itself when illuminated by a ray of poetry. All around us is asleep.’ But the problem may well be that ‘humankind cannot bear very much reality’. One could not stand the pressure of noticing how every particular object is capable of being revived, of being placed in a new context, whether poetic or not. The possibility is too challenging; it would lead to a radical restructuring of every act down to the habitual grasp of a cup of tea. The laboratories which depend on depersonalised objects, green walls and abstract concepts would suddenly explode in a fit of anthropomorphism. Even such stable abstractions as deoxyribose nucleic acid would stir into life. The act of posting a letter would become too complex with significance: a walk down the stairway, over the doorstep, on to the side-walk, across the pavement and over to the mail-box. Common objects would dissolve into their primal states, each having an independent life.

The most striking of these dissolutions occurs when an object has been put together through an ad hoc joining of parts. When we look at Picasso’s Bull’s Head, the fact that the figure can work as a bull’s head is always threatened by the parts that start to work as a bicycle seat and handlebars. Or, to take another example of using the bicycle seat in an ad hoc way, surgeons have created an Operating Chair-Stool out of pre-existing parts: an architect’s chair back, a bar-rail, an hydraulic pump, bed casters, car springs and so on. Picasso is taking advantage of the fact that the form of a bicycle seat also happens to work as the face of a bull, whereas the surgeons are using it for stability during an operation. One use is metaphorical, the other functional. Yet clearly, because of the multivalence of any object, the uses of this bicycle seat are hardly exhausted, although they are finite and non-arbitrary.

This is perhaps the most fundamental idea of semiology and meaning in architecture: the idea that any form in the environment, or sign in language, is motivated, or capable of being motivated. It helps to explain why all of a sudden forms come alive or fall into bits. For it contends that, although a form may be initially arbitrary or non-motivated as Saussure points out,2 its subsequent use is motivated or based on some determinants. Or we can take a slightly different point of view and say that the minute a new form is invented it will, inevitably, acquire a meaning. ‘This semanticisation is inevitable; as soon as there is a society, every usage is converted into a sign of itself; the use of a raincoat is to give protection from the rain, but this cannot be dissociated from the very signs of an atmospheric situation.3’ Or, to be more exact, the use of a raincoat can be dissociated from its shared meanings if we avoid its social use or explicitly decide to deny it further meaning.

It is this conscious denial of connotations which has had an interesting history with the avant-garde. Annoyed either by the glib reduction of their work to its social meanings or the contamination of the strange by an old language, they have insisted on the intractability of the new and confusing. ‘Our League of Nations symbolises nothing,’ said the architect Hannes Meyer, all too weary of the creation of buildings around past metaphors. ‘My poem means nothing; it just is. My painting is meaningless. Against Interpretation: The Literature of Silence. Entirely radical.’ Most of these statements are objecting to the ‘inevitable semanticisation’, which is trite, which is coarse, which is too anthropomorphic or old. Some are simply nihilistic and based on the belief that any meaning which may be applied is spurious; it denies the fundamental absurdity of human existence. In any case, on one level all these statements are paradoxical. In their denial of meaning, they create it. This may account for the relative popularity among the avant-garde of the Cretan Liar Paradox, the Cretan who says ‘All Cretans are liars’. It seems as if the statement is true, then it is false; if false then true. A very enjoyable situation, to some the essence of life. Yet by expanding the statement and avoiding its self- reference the paradox can be avoided. Thus Hannes Meyer’s statement might read: ‘Our League of Nations symbolises something, and that something is nothing.’ I say might read, because it is quite apparent from the context in which he made the remark that he meant that his building symbolised not all the previous ideas of government, but new ones based on utility.4 In any case, two points are relevant to my purpose: (1) that every act, object and statement that man perceives is meaningful (even ‘nothing’) and (2) that the frontiers of meaning are always, momentarily, in a state of collapse and paradox.

The first point is the justification for semiology, the theory of signs. It contends that since everything is meaningful, we are in a literal sense condemned to meaning, and thus we can either become aware of how meaning works in a technical sense (semiology), or we can remain content with our intuition. This dichotomy is probably a false antithesis since, ex hypothesi, semiology holds that we cannot be aware of, or responsible for, everything at once. Yet the goal of semiology, even if ultimately vain, is to bring the intuitive up to the conscious level, in order to increase our area of responsible choice.

The second point seems at variance with the first, for it appears to deny the existence of ultimate meanings (in its nihilistic stance) and it certainly undercuts the responsibility toward past, social meanings (except to upset them). To give an example, the position of Reyner Banham is relevant. In one book he starts a sentence ‘The Dymaxion concept (of Fuller) was entirely radical…’; in another, he says ‘Given a genuinely functional approach such as this, no cultural preconceptions…5’ Now these three avant-garde ideas, from a semiological (and factual) viewpoint, are demonstrably false. There simply cannot be anything created which is entirely radical, genuinely functional and with no cultural preconceptions (see below). Yet if re-qualified these statements would be semiologically acceptable and, more important, highly relevant. Because they point to that underlying experience where new meanings are actively generated and it seems as if one were totally free from preconceptions. Since there is a real sense in which this is true, one can agree with the emphasis on the radical and undomesticated. Except that, if taken as absolutely true, this tends to discourage a more radical creativity because it limits the area of criticism and active re-use of the past. It is one of the basic assumptions of semiology that creation is dependent on tradition and memory in a very real sense and that if one tries to jettison either one or the other, one is actually limiting one’s area of free choice.

Some of the main ideas of semiology will be outlined below, showing their relevance to meaning in architecture. What should be emphasised at this primitive stage of the subject is that the scope should be broad and inclusive. Semiology has to cover very general positions by necessity ranging from epistemology to physiology. This is necessary not only because there are pertinent assumptions right across the field, but also because such pursuits tend to fall victim to one limited orthodoxy or another (behaviourism for instance). But again, ex hypothesi, one is encouraged to use the various constructions of other semiologists to build a broad picture of how signs relate to meaning.

The Sign Situation

The first point on which most semiologists would agree is that one simply cannot speak of ‘meaning’ as if it were one thing that we can all know or share. The concept of meaning is multivalent, has many meanings itself; and we will have to be clear which one we are discussing. Thus, in their seminal book The Meaning of Meaning, Ogden and Richards show the confusion of philosophers over the basic use of this term. Each philosopher assumes that his use is clear and understood, whereas the authors show this is far from the case; they distinguish sixteen different meanings of meaning. To further underline this ambiguity another author has written ‘The Meaning of the Meaning of Meaning’ and one could imagine that inquiry being justifiably extended in length. But the point is clear: each use of meaning is different from any other and the particular case has to be understood from the context.

Thus, a doctor might say the meaning of a stomach-ache is hunger; a poet that the meaning of truth is beauty; a literalist that the meaning of ‘table’ is that sort of object to which he is pointing. It is this, apparently simple, kind of meaning which is the bastion of common sense and the tough-minded. Samuel Johnson, in a typically pugilistic mood, kicked a stone and thought he was thereby refuting the idealism of Berkeley. But, as Yeats pointed out:

‘… this preposterous pragmatical pig of a world,

Its farrow that so solid seem,

Must vanish on the instant did the mind but change its theme.’

This is of course a debatable point of epistemology.

For Plato, the object ‘table’ existed as a copy of some ideal, absolute table which itself existed in some absolute realm of ideas. As such, the object was at one remove the ideal table. Moreover, the painter who drew the table was copying a copy or creating a double lie (of sorts). Continuing Plato’s epistemology and morality for the moment we can see how many more times the word ‘table’ is removed from the ideal. Consider what happens in the sign situation in which we say ‘I see the table’. There is: (1) the ideal table of Plato, or the ‘thing in itself’ of Kant, or the ‘concrete set of events’ of the scientist – particles in motion at a certain moment in time and space (2) the ‘phenomenon’ of the table made up of light waves (3) of a certain spectrum which man can see (4) coming at a certain angle (5) just from the surface of the table (not the set of events) (6) which make an image on the retina (7) which is more or less adequate to our thought or expectation of a table (8) which is called by an arbitrary convention, the word, table.

Thus if we take this simple breakdown of the sign situation, we see that the word table is at least eight times removed from the thing in itself. Instead of saying merely ‘I see the table’, we should, less ambiguously, say something like: ‘I have an hypothesis about certain light waves out there which come from a surface which stand for an object we socially call a table.’ Of course this sounds ridiculous and we would be regarded as quite mad if we avoided the common and understandable contraction. But for speaking in such contractions and regarding words as part of things, we often pay a heavy price; as in the Cretan Liar Paradox, or the scientists’ hypostatisation of concepts.

This ‘abuse’ of language is really quite prevalent and can be traced from the politician's cliché to the astronomer who said: ‘What guarantee have we that the planet regarded by astronomers as Uranus really is Uranus?’ Or the architects who search for the essence of architecture, or the aesthetician who scoured the British Museum looking for what by definition all the objects must have in common: ‘beauty’. Perhaps the most convincing example of the power of signs is that of the shaman cited by Levi-Strauss.6 By the effective use of signs in a social situation the shaman can destroy another man without touching him: the sympathetic nervous system is upset, the blood pressure drops, food and drink are rejected, the capillary vessels become more permeable and the man dies without a trace of damage or lesions. All because a sign was effectively coordinated with a strong belief and social situation. Naturally most sign situations are less extreme than that of the sorcerer, but they are similar in theory and may even reach the same pitch as in religion, or on a mundane level, hypnotic trauma. In addition, the nausea due to misunderstanding a language, the fear due to unfamiliarity with a style, the conflict of generations, are all mild examples of sign shock.

Historically, semiology has been concerned with the right part of Figure 1; that is, basically, what happens when man perceives a sign through one of his five senses. Obviously most perception, particularly that of architecture and the new multi-media which are prevalent today, if a compound of several senses. In fact the present interest in unusual combinations makes semiology almost an inevitable study. It would grow from the happening, if not the laboratory. Yet, in any experience, one or two of the senses are bound to predominate, and for the present purpose we may discuss them together in general terms.

Thus in the usual experience there is always a percept, a concept and a representation. This is irreducible. In architecture, one sees the building, has an interpretation of it, and usually puts that into words. In each sign situation we can see language immediately entering and thus understand why semiology first grew out of linguistics. Following this course and using the model developed by Ogden and Richards, we can further articulate the right side of Figure 1.

The first point the authors make is that in most in cases there is no direct relation between a word and a thing, except in the highly rare case of onomatopoeia. That most cultures are under the illusion that there is a direct connection has to be explained in various ways. One explanation (see below) is Neoplatonic; another is psychological. In any case, everyone has experienced the shock of eating a thing which is called by the wrong name, or would question the adage that a rose ‘by any other name would smell as sweet’. It would not smell as sweet if called garlic.

But the main point of the semiological triangle is that there are simply relations between language, thought and reality. One area does not determine the other, except in rare cases, and all one can really claim with conviction is that there are simply connections, or correlations.7 Unfortunately more is claimed, much more. In fact the behaviourists hold that reality determines the other two, whereas the Renaissance Platonists claimed that thought is determinant. Each semiologist points the arrows in the direction he believes in, but, as the diagram shows, the relations are always two-way and never absolute.

A moment’s reflection on the history of architecture will elicit the relative autonomy of one area from another. Gothic form, for example, evolved and changed over 200 years without the content drastically altering. Then the Renaissance reinterpreted the content of Gothic – calling it barbaric, ugly, irrational – without changing either the form or the objects. Or, in our own age, the correlations have undergone an equally radical inversion. For instance, the Pop theorists and artists decided to change the pre-existing relation between form and content, calling all the previous detritus and trivia significant and vice versa. In any new movement, by definition, the pre-existing relations have to be destroyed and also, by definition, the older generation annoyed (even repulsed). The new generation must be confused. If there is not repulsion and confusion in the face of the new, then either it is not new or the viewer is uncomprehending. There is no third alternative if the semiological triangle is correct. What is interesting in the present situation (since this has always been known) is that the avant-garde has become addicted to the notion of change and the animated state of muddled suspension. They change the conventions faster than they can be learned or used, either in the belief that ‘that’s life’ or that it’s enjoyable. The logic seems binding. If one assumes that the artist must operate ‘in the gap between life and art’, and then that life is ultimately pointless and based merely on changing fashions, the results will naturally be an art which approaches fashionable life and sensuous appearance as a limit. One has to grant Pop Art and Neo-Dada their consistent logic.

Returning to the semiological triangle, we can see that if an overall interpretation is to be at all correct it will have to coordinate these multiple relations (which is by no means easy). Something may go wrong at any point. As Panofsky shows (Meaning in the Visual Arts, p. 34), we may be confronted with two similar objects floating in space which have two different interpretations. In one case this hovering, or rescinding the law of gravity, is meant to be an apparition or vision; in the other case, a real thing. Without knowing the conventions which support these different meanings we might reserve the intended relations and come up with the wrong interpretations. This is precisely what happened to Gothic forms in Europe for 500 years. They were very fruitfully misunderstood. Yet if correct understanding is our momentary goal, then we must be able to correlate correctly form, content and percept or, as Panofsky points out, the formal level of meaning with the iconographical (concepts, allegories) into a whole interpretation (what he calls iconology or study of the underlying symptoms and symbols of a culture). This sounds unwieldy and complex. In fact it would destroy an experience if we explicitly isolated meanings in this way. For instance the thirteenth-century semiologist, Durandus, might insist that each representation of Jerusalem be viewed in the following way: ‘Jerusalem in the historical sense is the town in Palestine to which Pilgrims now resort; in the allegorical sense it is the Church Militant; in the Tropological it is the Christian Soul; and in the anagogical it is the Celestial Jerusalem, the Home on High.’ An academic tour de force that, and yet the average pilgrim was meant to be able to do it. In fact in every age some such distinctions have to be made, since experience without abstractions is impossible. Thus in one way or another we are all condemned to academicism as well as meaning. The question is which and how? Postponing this for a moment we might speculate on one possible course.

If the study of how architecture communicates meaning process in accordance with past traditions and linguistics, then we might imagine the following set of abstractions. First, in every usual architecture there is always a form, function and technic.8 We may happily exclude for the moment all artificial exceptions to this rule, just as linguists exclude artificial from natural languages (the former being logic, mathematics etc.). In most architecture there has to be a form (comprising such things as colour, texture, space, rhythm), a function (purpose, use, past connotations, style, etc.) and a technic (made up of structure, materials and mechanical aids, etc.). Now, if the linguist tries to discover what basic units communicate verbal meaning and finds such things as phonemes and morphemes, then it would be highly appropriate if the architectural explorer found ‘formemes, funcemes and techemes’ – those fundamental units of architectural meaning. Whereas any usual language is doubly articulated, any usual architecture is triply articulated. The new field, naturally following linguistics, would be called 'architistics'. Some such analysis would be absolutely necessary if one were to analyse how architecture can communicate, and the only warning to be made about such a study is that it might well degenerate into academic formulae. The fictions might become rules; the function ‘functionalism’ or the form ‘formalism’. Since this is exactly what has happened in any case, it will have to be understood and explained.9

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Explanations of Meaning

Our explanation of meaning is meaningful depending on whether we concentrate on the left or right side of Figure 1. The intrinsic theory of meaning (the right side) posits a direct connection between ourselves and the universe. For instance the Gestalt psychologist Arnheim contends that because we are a part of the world it is conceivable that our nervous system shares a similar structure (or isomorphism) to forms. Thus a jagged line intrinsically means activity, whereas a flat line means inactivity or repose. The Platonists supported this kind of meaning and thus it is not surprising to find Renaissance architecture based on simple, absolute forms that were believed to carry intrinsic meaning (such as the circle which signified harmony and repose). By the same line of reasoning the Expressionist painter could claim that an all blue canvas meant sadness and a poet that the sound ‘bang’ meant the concept bang. However, in order to explain the all blue canvas that strangely signified joy, the painter would have to resort to conventions, or the extrinsic theory of meaning.

In spite of this apparent limitation, the intrinsic theory has had an extraordinary influence throughout history as the continual resurgence of Platonism shows. No sooner is it squelched than it sprouts another head. Rousseau wanted to re-align man with his intrinsic nature, Freud hoped to reconcile him with his natural drives, Jung with his inherent archetypes, psychologists with the structure of perception, genetic codes, common instincts and even reflex actions. This tradition has continually sought to find those universals and absolutes in man which determine meaning (Purism of Corbusier being the most recent case in architecture). And quite recently, the Psycholinguists have posited various inherent limitations in the mind which make certain language forms universal.10 If one puts the theory in its strongest form it would claim that a certain pattern intrinsic to man exists prior to and in more strength than a pattern in the environment. One only has to close one’s eyes and press hard on the eyeballs to see that this has a certain truth. But one would like to know how much. If there are certain favourable forms in man, then through some principle of psychic economy, extrinsic meanings should tend towards these forms. We would find that all languages and architectures had certain common attributes. We would find that all languages and architectures had certain common attributes. For instance, in most cultures, the red light, being intrinsically active, would mean ‘go’.

Since however the red light usually means ‘stop’ one has to resort to another theory. The extrinsic theory contends that it is stimuli from the environment which form meaning – the primary stimuli being language. Thus the way we perceive any object is determined by the concepts we have, or, in Gombrich’s terms, schemata. And instead of these schemata being an intrinsic part of the nervous system, they are slowly created through language and other cultural sign systems (or alone). A very convincing example of the way they work to create different styles (and thus ‘art history’) is outlined in Gombrich’s Art and Illusion. He shows the well-known example of the duck-rabbit which according to the schema of the viewer is either a duck or a rabbit, or both, separately – never together. A further interesting proof of the influence of schemata in perception arises when we try to see it as third thing, a thingummybob, neither duck nor rabbit.

This is actually quite hard to do because the schema, thingummybob, is not nearly so expected as the other two. Our language has stabilised the other two interpretations, which will not budge under such a puny assault. Yet supposing we wanted to start a new art movement and see the old duck-rabbit in an ‘entirely radical’ new way. We have the form, we want to change the caption. First we might muddle around in the animated state of suspension with the inadequate word ‘thingummybob’. Naturally this would bring cries of derision and contempt from everyone else who knew what it ‘really’ was, but we could bolster our courage by calling them all victims of their preconceptions. We could invoke a little manifest destiny and historical inevitability and show how Hamlet gets a new reading every year. The defenders of the two ancient concepts would be hindering progress, clearly anachronistic and out of touch with the present situation when all things are in flux. We strain, we half close our eyes trying all sorts of improbable combinations, until we hit upon a possible solution. Turned one way the figure might be a hand making the V sign for victory; another way a keyhole or bellows. Unfortunately, none of these new interpretations are as plausible as the first two, so they are rejected by society and we have to postpone our revolution. But any successful movement does find the new, plausible meanings; such as Archigram.

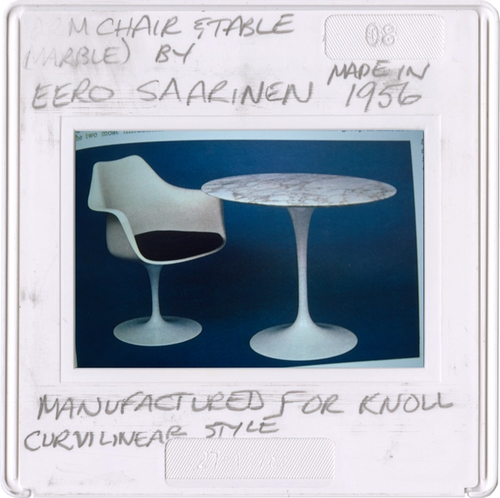

Consider some of the successful metaphors they have introduced into architecture. Cities which look like computer nets, robots, pneumatic tubes, bowels, telescopes, soap bubbles, comic books, space capsules, oil refineries, molehills and even the flexing tentacles of the octopus.

Returning for a moment to the extrinsic theory of meaning, it contends, in its strongest form, that schemata determine perception. That is, we are anything but passive receptors of outside stimuli, but always perceive them according to a former expectation. These expectations may be inborn, but mostly they are acquired. The most emphatic of these views is that of Whorf, who states that language shapes both thought and our knowledge of reality.11 While it is difficult, if not impossible, to prove this, there is a good deal of evidence which seems to suggest that it might be true. There is the test for colour perception on those who speak two different languages. The Englishman sees green, blue and purple, whereas the Navaho cuts up the same spectrum differently into /thatl-it/ and /tootl-iz/. He cannot distinguish the three colours (although he can be taught to), because he uses another language. Each language being different from all others, it stands to reason that each culture sees the world differently. The only problem with this theory is that, like the behaviourist one, it is nicely circular. We see the world differently because we speak a different language and vice versa. Which came first – language, thought, or reality?

The answer, I believe, is a little bit of all three. We form schemata by constant bombardment from outside stimuli, but also by relatively pure thought (logic, chess) and language. The hypothesis is the following: man has certain inborn dispositions to expect recurrent patterns, or to be more exact, he is always asking the environment questions. It is this curious purposeful side, which so completely permeates questions. It is this curious purposeful side, which so completely permeates his nature, that makes the passive, behaviourist position so ridiculous. This active, probing nature extends from concepts in the mind right down to perceptual schemata in the eye, or other receptors. Each level of this hierarchy acts as a sieve, only allowing those stimuli to pass for which it has a (figurative) hole – or schema.12 Initially these are the fairly open and undiscriminating, allowing any old stimulus to pass, but soon they learn. Thus the stimulus is continuously stripped of all its irrelevance and so we arrive at greater and greater generalisations.

The determination of what constitutes an adequate stimulus depends then on its relevance for the schema – how it is coded. For instance there are many examples all up and down the hierarchy of relevance selection: ‘Women were known to sleep soundly through an air-raid but to awake at the slightest cry of their babies.’ The slightest cry for an anxious mother constitutes an adequate stimulus; an air raid does not, so it is filtered out at a low level and repressed (the actual sounds do not reach the brain). Thus perception is partially goal-oriented even at this level, although usually the higher centres determine the goals.

To give a very rough idea of how this may work in perceiving, for instance, a pyramid, the rather simplistic trip of a multiple stimulus may be traced up the schematic ladder. Start with the first abstraction, that of the eye. The eye strips the image of its irrelevancies of retinal position. Because of colour and size constancy, other accidents of light and shadow are disregarded for more important Gestalt forms (such as outline and unity). Yet even here the image may be modified by attitude and we might see the pyramid as larger and brighter if it is of great value to us.

On the next level, the experience of motion may affect the image. Our eye adapts to uniform motion and, supposing we are moving at constant foot rate toward the pyramid and stop, it will tend to back up: this is because of our adapting schemata relevant to movement. Suppose then we suddenly close our eyes. The after-image of the three-dimensional pyramid will slowly collapse into a triangle. Or, if we are a particularly gifted people capable of seeing eidetic images, we could suddenly look to the blank ground and project a near perfect trace of the object – picking out all its salient features. Again, this is a short-term example of memory schemata but it is on a higher level than the after-image, because it is more detailed. In some cases it even approaches ‘photographic memory’. Yet such total recall, if relatively possible, can only exist with filling in by higher conceptual levels which are more abstract and symbolic.

About these it is hard to generalise except to say they are the most important. They may extend from some vivid image (the brilliant desert light shining on polished limestone) all the way to our attitude about Pharaohs and mass production. Lewis Mumford, who has criticised the pyramid builders for their bureaucratic subterfuge, no doubt tends to diminish and darken his view. In a partial sense then, knowledge and language determine what we see. But so do all the lesser levels of memory. What they have in common is their mutual interdependence and reliance on previous schemata.

We may say, along with Craik and Koestler, is that the main function of the nervous system is ‘to model or parallel external events’ and that ‘this process of paralleling is the basic feature of thought and explanation’. We slowly build up our schemata through a cyclical process of hypothesis and correction, all the time making our ‘model or parallel’ more habitual and closer to ‘reality’. Soon this schema may well become a habit or a skill. Perhaps a memory which is so well learned that it is as automatic as driving a car or playing with the rules of chess. In both these cases the rules of the game (or the ‘code’) have become so habitual that we can use them unconsciously while we attend to something more important (or the ‘message’). Or, to put it in Koestler’s terms, each schema is a flexible matrix with fixed rules which allows us to perceive each unique situation with a fair amount of flexibility. The more we look and concentrate, the closer our concept will approach reality. But the ‘reality’ that these schemata approach is still only relevant to the rules of the game. In Kant’s terms our schemata only allow us to see the ‘phenomena’ not ‘things in themselves’. When they work as an overall whole and are shared by a society or group, we have a ‘climate of opinion’ or ’myth’.13

In short, contrary to nineteenth-century thought, it is impossible to see ‘brute facts’ or ‘things, as in themselves they really are’. Contrary to what Marx, Gropius and Banham wished, it is impossible to get rid of all preconceptions. All we can do is substitute one pre-concept for another and bring it closer to a percept. This has very important implications, as Karl Popper has pointed out. It simply means that we can never know with certainty ‘absolute truth’. Not surprisingly the way science increases the scope of knowledge is through the same process of schema and correction, always testing a concept against a referent. The only time it comes in touch with the absolute is when it is proved definitely wrong; when a hypothesis is falsified. Otherwise, all the scientific laws and truths which we hold to be true are only unfalsified myths (which may however be in the privileged position of high corroboration). This view of knowledge coupled with Figure 1 helps to explain why the movement from Newtonian schema to Einsteinian was such a traumatic affair: the determinists of the nineteenth century thought they were in touch with ‘das Absolut’.

Context and Metaphor

There are two primary ways to cut through the environment of all sign behaviour. For instance fashion, language, food and architecture all convey meaning in two similar ways: either through opposition or association. This basic division receives a new terminology from each semiologist,14 because their purposes differ: here they will be called context and metaphor.

It is evident, as a result of such things as Morse Code and the computer, that a sign may gain meaning just from its opposition or contrast to another. In the simple case of the computer or code it may be the opposition between ‘off-on’ or ‘dot-dash’; in the more complex case of the traffic light each sign gains its meaning by opposition to the other two. In a natural language each word gains its sense by contrast with all the others and thus it is capable of much subtler shades of meaning than the traffic light. Still, one could build up a respectable discourse with only two relations, as critics have found. The perennial question of whether a good, bad symphony is better or worse than a bad, good symphony is not, as it appears, an idle pastime – simply because one adjective acts as the classifier while the other acts as the modifier and vice versa.

A similar analysis of architectural forms through simple opposition has been occurring over the last century. For instance, Wölfflin has analysed the opposition between Renaissance and Baroque in terms of five polar concepts, whereas Panofsky has analysed Gothic architecture (both over time and within a building) through the contrast of horizontal and vertical emphasis.

Developing this very simple model, we can show that the amount of meaning conveyed by a message is proportional to the unexpectedness of its occurrence in a context. Or, to put it differently, the more a message is expected the less informative it is: ‘clichés, for example, are less illuminating than great poems’. If the expectancy of everyone is slightly different, because of their differing memories, then it is natural that their experience of meaning will differ. Thus ‘one man’s meat is another man’s poison’ gains support form information theory.

We can see this if we watch our reaction to the generation of a quasi-ridiculous sentence. Start with the word ‘Twiggy’. We expect something like a verb to follow: ‘is’. Then the words ‘as busty as’ are not unexpected, all for reasons of sound, sense and syntax. We now have the highly probable beginning ‘Twiggy is as busty as…’, which because of its probability and triteness amounts to something of a boring cliché. Suppose we add the word ‘Billy’. This is rather a surprise in terms of sense, but not in terms of grammar because we expect a noun and a rhyming noun at that. Then, if we finish ‘Twiggy is as busty as Billy is lusty,’ we’re rather shocked because the comparison is odd. If we now substitute ‘spring’ for ‘lusty’ and ‘crashing’ for ‘Billy’, we have increased the information almost to the point of incomprehension. In an analogous way we can plot the surprise or meaning of a sign in any generative context which has a certain probability: a street sequence, for example.

The two obvious things to be noted about the way information is conveyed in such a sequence are that the amount of supporting cues or redundancy is high, so that we can miss a word and still understand the sense, and that information, or great poetry, always hovers on the edge of total incomprehensibility. For instance, some people might have mapped the second example as conveying no information at all, because they would fail to see how Twiggy could be as busty as crashing spring (what kind of ‘spring’?). Thus, on the paradoxical question of value, what information theory can do very well is make the paradox clear. Cocteau caught this conundrum when he said, ‘Tact is knowing how far too far can go.’

The other dimension of meaning is conveyed through associations, metaphors or the whole treasure of past memory. This is often built up socially, when a series of words conveys the same connotations in a language. But it also occurs individually through some experience of relating one sign to another: either because of a common quality, or because they both occurred in the same context (which would be the common quality, pace behaviourists). Thus an individual might associate blue with the sound of a trumpet either because he heard a trumpet playing the blues in an all blue context (the Expressionist ideal), or because they both have a common synaesthetic centre; they both cluster around further metaphors or harshness, sadness and depth. The behaviourist Charles Osgood (Measurement of Meaning) has thus postulated a‘semantic space’ for every individual which is made up by the way in which metaphors relate one to another. Thus he asks a Republican voter to plot his reaction on one issue (for instance, Dwight Eisenhower) against fifty-three key oppositions (good–bad, active–passive, etc.). These oppositions are further differentiated into seven parts so that one can answer ‘very good, moderately good… very bad’. In this very rough way Osgood can measure one reaction to various issues and plot a sort of frozen map of one’s current attitudes and the relation between them. He does not claim that we carry around such a semantic iceberg in our head, since our brain resembles that as much as a filing cabinet. But he does claim, with some legitimacy, that connotative meaning is relational.

To imagine what this might mean for architectural criticism, I have plotted a semantic space for certain architects, not because my judgement is important but because a critical consensus is formed through such overlapping of many semantic spaces and mine was the only one available at the moment. The immediate objections to the following diagram are obvious (Fig. 7). Why just the three traditional polar terms (form, function and technic)? We should know there are simply no rules or standards for good architecture, and all I have done is frozen my own prejudice and, as if this were not bad enough, had the naivety to make it clear. But this reaction rests on a mistake. If the past meaning of a word or sign is determined by all the matrices of which it is a part, and if these matrices must have fixed rules with flexible strategies, then the rules can be translated into a physical model and re-presented. It does not claim to show the present, immediate experience of meanings or those of the future. Furthermore, the model could represent a much larger, more important set, and the main reason I have settled on these three is that they are rather inclusive and can be shown in three dimensions (one could construct a hyperspace).

Multivalence and Univalence

The first point to be noted about Figure 4 is, as the activist would be quick to object, that it is static and dissociated. But this is the positive point: it is a univalent diagram where the whole (architect) has been analysed into a few isolated parts so that each one may be scrutinised. Whereas the experience of architecture is an indissolubly fused whole, the analysis is a fragmented, controlled separation. To insist on multivalence at the expense of univalence is to insist on enjoyment as the expense of science. A completely false alternative, since one can have both.

To concentrate first on the univalence of the diagram, one can see how architects tend to cluster around similar areas, which to my mind constitute groups of traditions. Secondly, my preference for the technical school is shown by comparing it with my distaste for the formalists. The latter is shown on the negative side of all three poles, not because it does not make positive efforts, but because in my judgement they fail (this is a diagram of prejudice). Lastly, Corbusier, Aalto and Archigram are far out on the positive side and thus explicitly show my preference. But this is not all. What it also indicates is that my experience of the latter inextricably links matrices which are normally dissociated. Actually it does not indicate, but implies, this.

When one sees an architecture which has been created with equal concern for form, function and technic, this ambiguity or tension creates a multivalent experience where one oscillates from meaning to meaning always finding further justification and depth. One cannot separate the method from the purpose because they have grown together and become linked through a process of continual feedback. And these multivalent links set up an analogous condition where one part modifies another in a continuous series of cyclical references. As Coleridge and I. A. Richards have shown in the analysis of a few lines from Shakespeare,15 this imaginative fusion can be tested by showing the mutual modification of links. But the same could be done for any sign system from Hamlet to French pastry. In every case, if the object has been created through an imaginative linkage of matrices (or bisociation in Koestler’s terms), then it will be experienced as multivalent whole. If, on the other hand, the object is the summation of past forms which remain independent, and where they are joined the linkage is weak, then it is experienced as univalent. This distinction between multivalence and univalence, or imagination and fancy, is one of the oldest in criticism and probably enters any critic’s language in synonymous terms. For it is an obvious division of experience at two ends of a continuous spectrum, the total involvement of all one’s faculties and the careful control of just one. Multivalence is of the greatest value in imaginative works and hence architecture, and univalence is of equal value in science. No doubt there are relevant qualifications to this, but in the main I think it is true.

What is disputable is the method of achieving it. The avant-garde insists on the destruction of all past preconceptions and matrices. But certain of them would go further. Having become committed to the quicker cycles of fashion and technology (in the name of 'reality') they would try to escape preconceptions altogether and approach random change and programmed noise as a positive limit. Often democracy, freedom and individuality are equated with this state of total mixed-upness. Yet this is the extreme of univalence, and if one does value creation or the ‘entirely radical’ (of which multivalence is an index), then one sees it as an entirely relative concept dependent on the past as well as its destruction. For the only way one can create a new matrix is by active use of those past codes, schemata, conventions, habits, skills, traditions, associations, clichés, and stock responses (even rules) in the memory. To jettison any one of these decreases creation and freedom.

Ferdinand de Saussure, Course in General Linguistics (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966), pp. 67-69.

Roland Barthes, Elements of Semiology (London, Cape, 1967), p. 41

Kenneth Frampton, ‘The Humanist v. the Utilitarian Ideal’, Architectural Design 38, no. 3 (March 1968): 134–36.

Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age (Oxford: Butterworth Architecture, 2002), p. 326; Reyner Banham, The New Brutalism: Ethic or Aesthetic? (London: Architectural Press, 1966), p. 68.

Claude Levi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology (New York: Basic Books, 1963), Chapter IX.

See for instance Robert M. V Dixon, What Is Language?: A New Approach to Linguistic Description (London: Longmans, 1966), p. 170.

One point on which architectural theorists have some sort of consensus from Vitruvius to Norberg-Schulz. See for instance Christian Norberg-Schulz, Intentions in architecture (London: Allen and Unwin, 1963).

See below ‘schemata’, or History as Myth, printed here. Charles Jencks, ‘History as Myth’, in Meaning in Architecture, ed. George Baird and Charles Jencks (New York: George Braziller, 1969).

Charles E. Osgood and Thomas A Sebeok, Psycholinguistics (Indiana University Press, 1965), p. 301.

Benjamin Lee Whorf, Language, Thought, and Reality (MIT Press, 1956).

For this theory, the quotes and a similar analysis, see Arthur Koestler, The Act of Creation (Pp. 767. Pan Books: London, 1966), pp. 520-48, p. 624.

See Jencks, ‘History as Myth’.

For context other semiologists use syntagm, metonymie, chain, relations, contiguities, contrasts, opposition; for metaphor they use association, connotation, correlation, similarities, paradigmatic or systemic plane.

Ivor Armstrong Richards, Coleridge on Imagination (London: Kegan Paul & Co, 1934).